Professor Kathleen Culpo teaches in the Department of Health, Human Movement, & Sport, and she is the Health Education Program Coordinator.

Professor Katy Culpo describes it as an “aha moment” when she realized that she was sick of just talking about concepts in her Health Issues course. As she puts it, she wanted “a little less talk and a little more getting them to do something about it inside and outside the classroom.” Professor Culpo shares some helpful ways to incorporate activities that promote student wellness into the day-to-day experiences of her course. It is an instructive model for guiding students to apply course concepts and transfer them to situations beyond the course.

Here’s an example of what she has in mind:

Incorporating movement into a reading and discussion activity: In Health Issues, Professor Culpo’s students read articles and reports on such subjects as the harmful effects of alcohol abuse or on cannabis use and its impacts on the growing, adolescent mind. She prompts the students to react to what they are reading, to notice their own “aha moments”, and then to write notes to themselves right there on the paper in the margins. When they come to class, she escorts the students to the nearby gymnasium and gets them walking laps in small groups. As they walk, the students refer to the paper margin notes and discuss what they wrote about. When they return to the classroom, the groups share out what they have discussed, and she assures that they have hit the high points of the reading. She then collects the actual readings with their notes for further assessment.

Since the class meets at 8AM, this activity gets her students up and moving. Professor Culpo explains that this kind of movement assures the circulation of oxygen-rich blood to the brain, creating conditions much more favorable for cognition and long-term retention. As she says, “movement is fertilizer for the brain.” The idea has many applications. Professor Culpo urges her students to think about how they can incorporate kinesthetic activities into studying, for example. Thinking about how instructors could use this idea, she imagines that this kind of active small group work could be done outside the classroom anywhere on campus.

But there is even more going on here than meets the eye.

Using “Brainbreaks” in class. Periodically, Professor Culpo will pause class, produce her “Brain Breaks” jar, and ask a student to draw a card from the jar. The card presents a set of instructions. Here’s an example:

1) Stand up;

2) move to clap your hands,

3) but miss and cross your arms;

4) turn your hands so that

5) your palms grasp to

6) hold your arms crossed.

7) Then, wave your arms from side to side.

Professor Culpo knows what her students might think about these “crazy activities.” That’s one reason why she explains very early in the course what is happening in their brains while they do them. This clapping hands activity is one of many research-based activities that engage both hemispheres of the brain and focus students’ attention on their movements, giving them a cognitive break from the class topics. The activities provide tactics that they can do on their own outside of class to maintain concentration when they study. Thinking about how the brain break works is also an opportunity to apply what they are learning about movement and how it affects the brain. Further, pausing to reflect on the activity is an opportunity for metacognition and transfer as they think about how this can be applied to their day-to-day experience.

The 30-Day challenge: As a way to apply and integrate these activities into their daily routines, Professor Culpo uses her (now campus-famous) “30-Day Challenge” activity. In the challenge, the students are asked to make a small change in each of six areas of wellness, ranging from how they sleep to their use of alcohol and other substances. In addition to making small changes, the students are prompted to reflect on their success and to do so regularly, assessing how easily they maintain the change and how they are feeling as they are doing it. Students complete this activity during the first weeks of the term, but they return to it again for another 30-day challenge later on in the term. In this second run, they choose their own changes to enact in each of the wellness areas, reflecting once again on how the practice is making them feel. If you are interested, you can download example templates of the activity here.

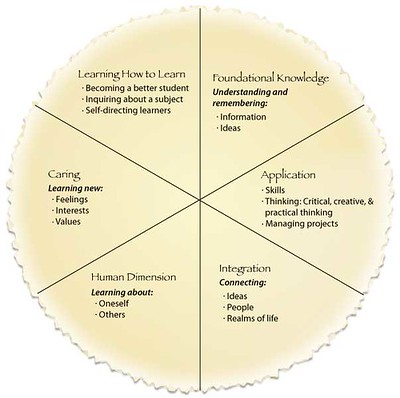

The core idea here is to produce lived experiences that are built into the learning of the course. The approach provides a holistic vision of health and wellness and also one that engages students in practicing a growth mindset. And, as the students learn by reading research studies in the class, there is a direct correlation between these kinds of simple wellness habits and student success. As Professor Culpo says, “sometimes people tend to think that because they are alive they know how to live in healthy ways.” In Health Issues, Professor Culpo builds the foundations for her students for careers in health professions, but, really, she is teaching them the habits that accompany happy lives.

If you want to learn more about some of the theory behind these activities, Professor Culpo recommends The New Science of Learning: How to Learn in Harmony with Your Brain, a book written for students by Todd D. Zakrajsek and John N. Gardner.