By Chris Boettcher

Even before preparing for this week’s issue of The Educator, we have been taking stock of an essential subject: how our teaching can be responsive to the ongoing conversations and conflict about race and diversity in our community.

It goes without saying that the topic can’t be treated in a “pedagogy tip”.

But maybe the “tip” this week is just to get started.

I say this knowing full well that for some of us it is difficult to see where to start or even the right way to go about starting. It is a challenge that requires care, ongoing practice, and persistence. The Center for Teaching and Learning is committed to providing resources to help you, and this subject will directly inform our agenda for December and January planning.

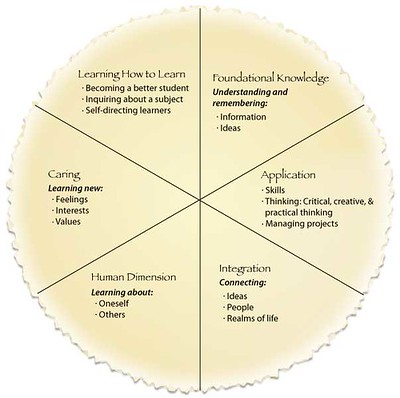

For me, the word “pedagogy” always carries some of the meaning that Paolo Freire described in Pedagogy of the Oppressed. Freire famously compared his ideas of pedagogy to what he called the “banking concept” of education. The metaphor imagined “teaching” as making a “deposit” into the empty minds of students. It is a transaction between “expert” and “novice” that shapes their relationship to one another and to the knowledge of the classroom. Freire saw this relationship mirrored in the broader structures of oppression of colonizer and colonized subject. He proposed the idea of “pedagogy” as a liberatory concept. In the practice of pedagogy, as opposed to teaching, students would not be thought of as subjects in need of being “taught” but as active learners and co-creators of the learning taking place in the classroom.

No matter our posture, violence and hate, experienced or witnessed, erupts into our classrooms. Our students may come to class angry, elated, or suffering. If we can marshal the courage to give space to their feelings, to provide a place to unpack and process and make sense of their lived experience of our world, we do our students a great service. But this leveling can only begin when educators allow themselves to become vulnerable, and it can require entering into a new relationship with learners through humility and self-reflection.

So, where to begin is to commit to begin.

It is extremely important to interrogate our own positions and beliefs, explicit and implicit. It may be valuable to learn more about how racism can manifest in the college classroom or to learn more about your own implicit biases.

We need ongoing practices that build a sense of safety and inclusion the classroom environment. A quick search finds plenty of bulleted lists on how to create a safe classroom space and lots of adjectives to describe it, but the work is difficult. It requires intentionality and constant upkeep. As an example of such a practice, I often point to the group agreement as a place to start. It is not just a good classroom management technique but also a tool through which you can surface students’ expectations and experiences. It also begins and a metacognitive discussion about how participants will interact with one another when the difficult conversations take place.

Thus prepared, there is possibility of a space where we and our students can speak and listen to one another, to put words to experiences as a way to give voice, hear, and interrogate them. Opening a classroom space to productive reflection takes work. For techniques, I draw on the literature of service-learning and community engagement.

Here is an opening technique: if you are prepared to engage in a discussion, ask students to write for five minutes (more if you have a practice of freewriting in the course) in response to a provocative question or prompt. After they have had this opportunity to gather their thoughts, begin by asking them about what they wrote or their experience of writing. What did the writing make them feel and why? What were they thinking about as they wrote or to what insight did the writing lead them? A sound strategy is asking everyone to share something, without comment, until everyone has spoken at least once. If you can find a way to share written thoughts for students to discuss, it can create that critical distance where listening and dialogue can begin to take place.

For now, it’s a start.

[…] Pedagogy Tip: Starting with Difficult Discussions […]